I reached for the edge of a hole in the face of the rock, a hollow worn into the sandstone over decades of rain and wind. It was the perfect hold, a bulky edge I could wrap my shaking fingers around. After several vertical meters of forcing my sore fingertips into only tiny grooves and narrow cracks, I was relieved to be able to lean back in a stable position. I reached behind my back and dug in my chalk bag, coating my fingers as I looked up, scanning the rock for my next move.

A breeze snaked down into the gully below me where my husband stood at the other end of my rope, his able hands relaxed but poised at the belay. I smeared the toe of my right climbing shoe against the rock to get a better grip and rotated my shoulders to glance down at him. His hair ruffled in the wind.

"Looks good, honey," he called up to me. Behind him, our friends Jeff and Amy prepared for the next climb.

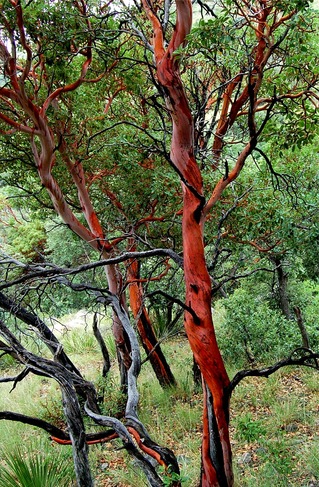

The route had started as an easy, even 5.7 lie-back. Sandstone is notoriously slippery, but this corner of the park was heavily shaded by pines, oaks and madrones, their trunks veiled by a tangle of green and gray lichen. In the shade, our dry fingers and palms caught even the smaller holds easily.

Higher up, sunlight found its way through the canopy and baked the rock face. It reverberated brightly under our bellies and forearms, pulled sweat to the surface of our skin so that we had to wipe our hands against our shorts and shirts before making the next move. The glare made it hard to see the chalk echoes where other climbers had marked the way.

I turned my focus back to the climb and muscled my way up, making the most of the big hold. I pulled myself over the edge of the hole in the rock and discovered a cavern, dark and deep, much larger than I'd expected.

---

Earlier, as we'd approached the base of this popular climbing spot, Jeff had remarked his surprise that we were the only ones there on a Sunday afternoon. We flaked out our ropes and yanked on our harnesses, laughing over our good luck. Jeff led the climb, pausing every so often to place protection in the rock and clip his rope through. We watched him swinging his arms up and pressing his knuckles white as he gripped the small, grainy numbs of the rock. Amy sat on a boulder and tilted her chin back, gazing at him with wonder and pride. I know that look. She and Jeff are getting married in a few short months. It's the look of a woman in love, a woman who is blessed, a woman who knows that she is a blessing to the man in her life, too.

Jeff had secured himself at the top of the route and called off the belay, and knelt down to pick up what appeared to be a glossy piece of paper.

"Did you take reading material up with you?" I called up to him. "What is that?"

He had mumbled something, turning the paper in his hands so that it reflected light up onto the trees.

"What is it?" Amy asked, louder.

"It says this route is closed," Jeff answered, still not looking down at us. He continued, "It says something about protecting the wildlife."

He peered down and we peered up, studying the way he'd gone. The stone stared back at us, blank and gritty, heavily chalked in places. There were no delicate patches of quivering flowers, no lacy webs of lichen or moss, no muddy swallows nests clumped under the eaves of the cliff.

"I don't see anything that needs protecting," he said. "It may be an old sign. Besides, it's only this one route. Everything else going that way is open." He gestured to the other bolted routes to our left.

"Maybe we shouldn't climb it," I protested. "Maybe it's something we can't see."

"Nah," said Jonathan, shaking his head. "He's already built the anchor. Let's just climb this one and then move down the rock."

---

Knowing that falcons and hawks often nest in cliffs, I tensed and prepared to drop out of the hole into a rappel stance, but the nest was abandoned.

The rank odor of carrion pulsed in that still space, shadowed by stale scent of droppings. My eyes watered and I could barely make out the tiny, intricate black and gray pellets that pebbled the surface and piled in the corners. As my eyes adjusted, I could see rocks and clumps of fur and white fluff, dead leaves and sticks, and fragments of shell scattered across the floor. A single feather lay close to the wall nearest me. One long, curved, silver-brown feather trampled and coated with dust.

"I know why they closed this route," I said loudly and over my shoulder, never taking my eyes off the cavern before me. "There's a nest up here. Or there was."

"What kind of nest is it?" asked Amy, a former camp counselor who knows the intricacies of the Pacific forests the way a genealogist might know her ancestry, broadly and intimately all at once. Before the afternoon ended, Amy introduced me to a banana slug, helped me navigate around poison oak, and showed me how to cool my damp, sweating skin by hugging the cool, smooth, trunk of a madrone tree.

While Amy knows the woods, however, I know the birds. In my house growing up, the "good book" was the

National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds

. My folks taught us to identify individual species by their feathers, wing span, stature, silhouette, tracks, droppings, calls, and nests.

But atop that route, I was stymied.

There was no structure to the nest. No solid, well-crafted stick-and-mud bowl lined with soft feathers and grasses. No warm, unblemished eggs secured from the elements. No mother bird settled, plump and protective, over her young. No beguiling, fuzzy heads peering out at me with bright curiosity.

But I still knew, deep in the meat of me, that while this pit I'd happened upon wasn't quite a nest, it was still a den, a hovel, a pit of habitation. A home.

And the master of that home was big. I could tell by the brown and silver feather that ran the length of my forearm; I could tell by the drag marks in the gray dirt floor where meals had been pulled up and in for her young.

"I don't know what it is," I said loudly over my shoulder. "But it's not here anymore."

With my free hand, I caught a small clump of white down, as fine as a whisper, between my fingers and held it up to the light. There was a lot of it in the cave, scattered and snagged on the sticks and in the dirt. It meant the chicks had molted, fledged, left the nest.

---

Back at the base, I unharnessed and grated my hands over my back pockets, back and forth. Mosquitoes hummed and whined in small clouds around our ankles, shoulders, the backs of our knees. We were stoic, having misted ourselves with bug spray before beginning the trek. Soon, though, we began swatting and slapping at them, whiffing the air with clumsy, quaking hands. Amy and I shook our heads and let our pony tails swing over our necks. She roped in and began to climb, ascending quickly to get above the bugs.

I winced at the narrow peal of a mosquito coming in for the harvest. A succulent silence followed as I hunted for the harvester. With an authoritative clap, I flattened him and flicked his remains off into dust. I moistened the tip of my index finger, wrinkling my nose at the tang of bug spray residue on my tongue, and wiped away the crime scene, a delicate red flare of blood on my bicep.

"So what do you think was nesting up there? An eagle?" asked Jonathan.

"I don't think so," I said. "Eagles aren't prevalent in this area. Besides, if this route were closed to protect eagles, that paper would have been much more specific. There's probably a fine for disturbing baby eagles."

"It's a neat topo," Jeff said, referring to the laminated paper that had been bolted at the top of the formation. "I sorta wanted to tear it off and bring it down." He sat into his harness and pulled the rope taut for Amy, who had paused in the sun halfway up the route.

I looked up at the sky, pooling blue between the dark tree branches.

"Whatever made that nest is big," I said, puzzling over all that I'd seen. "Maybe a hawk of some kind, but they usually prefer to nest in the tops of dead trees."

Amy's feet slipped and scrambled on the sandstone.

"Looking good, Ames," I yelled to her. "You're doing great!"

She righted herself and pulled up and around the corner into the den in the rock. "Ugh," she groaned. "It does smell foul in here."

Something dark carved a wide turn in the sky above us, blinking through the leaves as it passed between us and the sun.

"Whoa," I said, quietly. It swooped by again, much nearer this time. I began turning around and around trying to discern the movement and direction through the trees. The next time, the shallow V of the sweeping wings was a dead giveaway.

"Turkey vulture."

Vultures are the untidy, unkempt, ugly cousins of eagles, hawks, falcons and other birds of prey. They scavenge for their food, and so they have the same sullied reputation as hyenas, flies, and cockroaches. They are considered cowardly, the harbingers of death and evil, all the more ominous because their flight is silent (they rarely flap, relying instead on their massive wings to harness thermal currents in order to keep themselves aloft) and they lack the vocal equipment to do anything more than hiss and grunt. . Vultures lurk for hours and days, swarming above a dying animal and only landing when life is gone and there is no chance of a fight.

But this vulture wasn't descending to feast on a carcass. She'd been out all day foraging for food and had returned to check on her nest only to find a group of colorfully clad, rambunctious climbers scurrying up what she'd hoped was an impossible vertical cliff of stone. She was descending to scare us off.

The vulture careened onto a flat patch of stone far to the right of the cave I'd visited and hobbled out between the boulders to glare at us. Her head was red, wrinkled, and devoid of feathers to make rooting around for meat scraps between the ribs of a dead animal an easy task. I loathed her baldness. I loathed her dark purple eyelid when she blinked at me.

Jonathan and I laughed and kicked up dust as we tried to get a picture of her.

"What is it?!" cried Amy.

"Turkey vulture," I answered. "It's a vulture nest!"

"Should I be worried?" she asked, craning her neck for a view of the approaching buzzard.

Before I could answer by asking Jeff to lower his sweet fiancée quickly, something else moved off to the right, coming up and out of another outcropping of sandstone, nearer to where the vulture sat, hunched and angry. A large vulture chick hopped onto the rock and into the sun. He was awkwardly proportioned, with large, brown and gray feathers poking painfully out between tufts of white down, his wings coiled tightly against his body. His head rolled on his skinny neck and he crouched down to hiss at us, at the trees, at the world.

A new lesson swirled up into my consciousness. Vultures, like many of their more beautiful and more oft considered brethren, sometimes nest in large groups. The red head of Mama Vulture was still trained on us. I smiled at her. She was protecting her young. Suddenly, her red head and purple eyelid seemed less grotesque. I knew that when she flew into the sun, her brown-gray feathers would sparkle silvery-white and her gargoyle hunch would give way to a grace only found in the sky.

"No worries, Ames!" I answered. "She's not here for you. Steer clear of the nest and we'll move over to a different route after you're done."

---

Afternoon dimmed the sky. Jonathan led a very difficult route and we each took turns following him up. The mosquitoes became more plentiful and white welts popped up on our skin, visible even beneath the film of sweat and dark dirt. We packed our bags and hiked up out of the gully to meet Jonathan, who had climbed up last to tear down the anchor.

Poison oak choked the spaces between the boulders. The Acorn Woodpecker, an able lumberman in a jaunty red cap, tapped out his hungry rhythms at the top of a tree. The sturdy Steller's Jay bounced from limb to limb, his shadowy blue feathers mimicking the sky. We followed the light up the trail, stepping over mossy logs and startling at the now-you-see-it-now-you-don't of black bats fluttering after bugs.