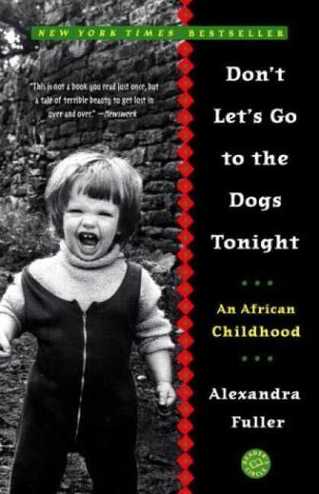

The cover of the current edition of Alexandra Fuller's Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight is split down the middle by a vaguely tribal design, the title to the right and a black and white baby picture of the author on the left. Young Bobo Fuller's mouth is wide open in a squall and her shoulders are squared for battle. If this photo were described by the author, though, she might say that the child's shoulders are battle-squared and her mouth is screaming-wide.

Fuller is masterful when it comes to compounding her descriptions, harnessing her adjectives to one another with hyphens. Her word choices are simple, words that are familiar to one whose childhood hinged on a wild, sometimes barbaric plain, and rose from a landscape peppered with gunfire and dotted with packs of dogs. She describes her childhood in these terms. The patted-down red earth. The boiled-meat smell of dog food. The neck-prickling terrorist-under-the-bed creeps. The oven-breath heat. These hyphenated descriptions set the tone for the memoir.

She writes in the first-person present-tense, but the tone is not omniscient and looking-back, the way one might think an adult memoirist would write about such tormented circumstances. Rather, she calls upon the way a child would describe what she sees. This is especially true when she recalls her mother:

Mum sitting "yoga cross-legged" as her beloved dogs sit "prick-eared" and watching. And after death of baby Adrian, once the family moves back to "working-class, damp-to-the-bone Derbyshire," it is Mum "sleeves-rolled-up running after two small children" (37). And upon the family's return to Africa, Mum is "don't-interrupt-me-I'm busy all day" (42). These are word portraits, culled by a child watching her conundrum of a mother as she ages, pulls through the death of a second child, and devolves from "being a fun drunk to a crazy, sad drunk" (93).

Fuller tells us that her "life is sliced in half. The first half is the happy years, before Olivia dies" (94). But the author was only ten-years-old when her little sister drowned in a duck pond, rendering young Bobo to a life of guilt for allowing it to happen, for being responsible for Mum's madness. If her life was halved when she was ten, it means she considers those first ten years with as much importance as the rest of her life, that those ten years cling to her.

Africa as seen through the eyes of an inquisitive, observant child is beautiful. Of course, so much of the history of Rhodesia/Zimbabwe can only be related by an adult, but the details, nose-to-the-earth details described by an eager, scarred child are lovely in their melancholy. A bossy, hands-on-hips white madam. Skin-pinching dehydration. Smokingdrinking parents. Lichen-dripping trees. Fertile-foul smelling earth.

The special traumas and violence of Africa, too, are told in this lilting, innocent, observant voice. Her family has witnessed the aftermath of landmine explosions on the roads. Fuller and her sister "heard the damp-dead sound of the heavy flesh hitting the ground" (58). The author, an adult Fuller who has traveled the world, married, and returned to Africa, remains haunted by what she did not see, what she only heard from her older sister, Vanessa, who told young Bobo to hide her eyes as they drove by the carnage. Fuller thinks "of dead bodies as strips of meat hanging land-mine-blown from trees like strips of drying, salted biltong" (58).

What I appreciate most about all of these descriptions is their accuracy. They are deft and true. I can envision all of it. I smell what she wants me to smell. It's honest.

I opted to read two memoirs prior to this deadline rather than reading a craft book because, after reading Dogs, I read Fuller's statement at the back of the book regarding Michael Ondaatje's influence on her work. How he inspired her honesty by "[laying] open the soul of his family... with humor and affection and, above all, without judgment"(309). Because Fuller's own stark, exacting-but-gentle style impressed me, I knew I had to move on to Running in the Family immediately, to meet the master who inspired the woman I now consider a master.

Last week, I sat with two friends and two bottles of wine. We talked late through the night and into the following morning, sharing stories about our respective families. The embarrassments we've suffered. The characters we come from. The sordid details we know now about parents, details which were previously kept from us. We were too young, but are no longer.

As my friends and I talked, our hands flapping and fluttering through the tales we spun around the glasses of wine, I considered the element of betrayal. I love to tell a good story. I'll craft them for years and deliver them succinctly, with specific word choice, for ultimate impact on my audience. But they are often watered-down. I don't look or cut too closely, lest it fall apart around me, shattered by angry parents, betrayed siblings, indignant friends--all the characters of my stories.

Witnessing Fuller's recounting of details more torrid, more sensitive than anything my family has or hand to offer, and witnessing her grace and utter lack of criticism in the telling has inspired me. I will take away not only her honesty and humility, but her uncannily perfect descriptions of the simple things.

My favorite:

"The springer spaniels make repeated attempts to fling themselves up on the visitors' laps, and the missionaries fight them off, in an offhand, I'm-not-really-pushing-your-dog-off-my-lap-I-love-dogs-really way" (82).