When whispers of the rise of Hitler were born deep in the desolate heart of Germany, they rose to the surface only slowly, aided by the rediscovered "patriotism" in the hearts and minds of post-WWI society.

When whispers of the rise of Hitler were born deep in the desolate heart of Germany, they rose to the surface only slowly, aided by the rediscovered "patriotism" in the hearts and minds of post-WWI society.

Early in the 1930s, young Adolph Hitler was a gem in the sunken crown of Germany's government. His voice was the first commanding, positive sound the impecunious, hungry, pessimistic people had heard since their defeat more than a decade prior. And as the energetic, ambitious leader took control of more and more power, the contagion that was his message took hold on the weak populace.

A world away, Americans could barely hear the far off echoes of tiny avalanches on The Continent. Rumors came by way of radio, newspapers and, above all, letters from friends and family overseas. Being a country of immigrants, almost everyone located in the United States in the 1930s had some relatives in Germany, France, Poland, Italy, Austria, Hungary, Denmark, Holland, Sweden, Russia.

In the beginning, when news was slowest, people were loathe to condemn a move by the heretofore isolated German people to reclaim their former place among the world's great nations. Hitler was just another politician with a dream. The Great Depression had Americans, as well as peoples worldwide, in a death grip. Our President was distracted by the poverty and the public outcries for support. After all, the Germans had no money, no military, no allies. How much trouble could this fallen country really cause?

In 1938, an American woman named

Katherine Taylor

was inspired to write

a story which took the burgeoning Third Reich and its leader into

consideration. She'd read a news story about American students in

Germany who had written letters to friends at home, telling them the

"truth" about Hitler and his dark, terrible hope for Germany. When

those friends wrote back, allegedly teasing and mocking the German

government, the response from the students in Germany was sobering.

"Stop it. We're in danger. These people don't fool around. You could

murder [someone] by writing letters to him."

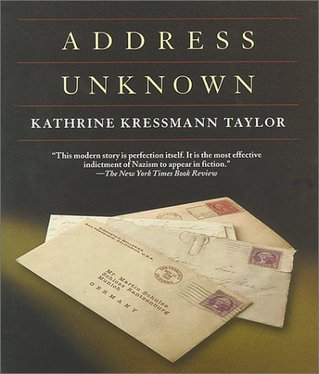

Taylor's subsequent work of fiction,

Address Unknown

, is written in the

form of letters between two middle-aged German men, Max and Martin. The story opens as

the two are separated for the first time after living in America as

best friends and co-owners of a successful business. Martin has

returned to Germany to help rebuild his home country. The year is 1934. Max, the one who remains in America, is a German Jew. Their correspondence

over a four-year time period is beautiful, succinct, brutal... and

twists through the rugged terrain of politics, familial duty,

patriotism, and

anti-Semitism

.

Ms. Taylor's story was published in 1938 under the name Kressman Taylor

(apparently because the subject matter of the book was too serious to

be distributed under a female name).

Address Unknown

was an immediate

success.

By that time, of course, the news out of Europe was no longer the stuff

of rumor. The atrocities were real. An entire race was a target of

Hitler's wrath. War was inevitable.

I read this book in a single hour, swept along by the swift, able

prose. And, while I will not spoil the impressive plot manipulation, I

can tell you that what happens is more than plausible. If you take the

chance to read this little book, allowing yourself to remember a time

when the world was not at your doorstep and mail took three months to

arrive, you'll feel the heart of this story pulsing in your hands.

Address Unknown

should be read as history, an excellent underscore to

the dry, factual texts students are subjected to in high school. In a

textbook, the Holocaust can be read as merely regrettable, especially

as we move further and further from it. Numbers and statistics can be

memorized, but the subtleties of this little book are haunting. In a

few select words, Ms. Taylor amplifies the agony of a world forced to

deal with hatred born of desperation, bringing it to an unavoidable

volume.

I will never forget this short story. It has marked me.