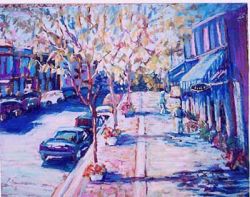

Sunlight on brick is hottest at four in the afternoon. It bakes between the boxy shadows of the buildings on Main Street. Boys sip coke from slender-necked bottles. One of them shakes his fist, rattling the dice and tossing them down to clatter up against the wall. Two sixes. As there are no rules to this game yet, he'll come up with them later, he smiles and takes them up to roll again.

Sunlight on brick is hottest at four in the afternoon. It bakes between the boxy shadows of the buildings on Main Street. Boys sip coke from slender-necked bottles. One of them shakes his fist, rattling the dice and tossing them down to clatter up against the wall. Two sixes. As there are no rules to this game yet, he'll come up with them later, he smiles and takes them up to roll again.

Women move slower in the heat, but they allow their hips a bit more swing. This is to catch the only breeze with their pastel skirts; catch it and let it flutter between their knees, cooling their muscular ankles. From beneath the brims of their day hats they talk the way only women can. Words like soft bubbles float between them, many at a time. To the words they nod. It could be gossip. It could be education. It could be nothing at all.

I wonder at these people, the ones who move by me without looking back. They would only see a little girl with her hair snarled into something like a braid. They might see my freckles or my chocolate brown eyes. But I doubt very much they would see me. I do not translate well into words the way they do.

One man hefts a crate of newspapers. He is the owner of the market, and those newspapers no longer possess the news. What happened this morning is long gone. In the heat of the afternoon, people do not care about anything but the baseball scores, and they'll catch those on the radio this evening. Or they can stand in the doorway of the barber shop and listen in as he gives free haircuts to the only three White Sox fans left in our town.

Mr. Charles and his wife live above the market in an apartment with only three windows. Behind the store in a planter box, Mrs. Charles keeps a very small Victory garden. When she took the train to Springfield to visit her mother for a week, I stopped by and watered the tomatoes after school. On my last day I tied a red, white and blue ribbon to the top of each plant. The plants have outgrown the ribbon now, and it's tattered, but Mrs. Charles won't untie them. She says that patriotism must be able to withstand wear.

If I take careful steps, the long kind, so I feel a pull just behind my knee but both feet are flat on the ground, it takes only thirty-two to reach the corner where my house is. The two blue stars hang in our kitchen window above Mom's white porcelain duck. One star is for my brother, Henry, and the other is for Uncle Thad. When we're sitting around the table at dinner now, since last December, Dad tells us to hold hands and then he says simple words to God. He never asks for a thing, but instead speaks what he hopes he knows. Henry is safe. Thad will be home soon. Those goddamned Nazis will lose this war.

Sometimes I don't keep my eyes closed all the way, and I see Mom wince a little when he swears. But I also see her mouthing her own prayer. She asks things, so I do, too.

Our table cloth is sky blue with little eyelet flowers. When dinner is over and everyone is gone, I help to clear the table. But I get the napkins last. The crumpled white napkins look like clouds on the blue tablecloth sky. It makes me think of Henry and his plane, the way the engine sounds like a thousand snaps being pushed closed and ripped back open all at once. His uniform looks like that sound, all snaps and razor sharp creases down his long pant legs. His picture is on the piano and his cap is cocked to one side. He is next to his plane, which looks like it is baring its teeth; and I think he looks so dashing.

But that is all I think of this war. If I think much more about it I'm afraid I'll become bitter. I could even start to stoop a little, like Mrs. Macklin does because she's always leaning in to hear the war news on the radio. Instead I skip rope and walk along the curbs like they're tightropes. On Tuesdays we go to the community center pool.

I love to swim, and Mom made me a red bathing suit that looks just like the one Betty Grable wears in her most recent movie, but I don't look at all like her. Too small in so many different ways. The boys at the pool don't look at me, but like I said before, they wouldn't see me anyway. Until last month the boys went to the pool to watch Hannah Stuart. She's the only one in our town who owns a bikini. But then she went off to be a nurse in the navy. Both of the Levi brothers enlisted that same week, but that was probably a coincidence.

Today, though, I am merely sitting on Main Street. A lady in a pink dress and a yellow hat is buying a water melon, but she seems to be having trouble picking exactly the right one. When I am older I hope I learn how to do those grown-up women things, like applying mascara or picking out melons or placing strips of cucumber by the door so the ants won't want to come in. I can't do any of that now.

What I can do is watch. I see things and know things so fast that the words just come from nowhere, from that secret spot in my brain where I never sleep. And I remember all of it. I remember the way the chalk clicked and broke in half in Ms. Silver's hand just before she dismissed our Sunday school class on that weekend before Christmas. Dad was waiting for all of us in front of the church, even though he never goes. He'd walked over and he was out of breath. He was holding Mom's hand and squeezing, and then they led us down the street like ducklings. I shuffled my feet along to make scratchy, soft-shoe music. I remember Dad sitting us down on the sofa and explaining the word infamy.

My peppermint ice cream has melted into a pink puddle in my glass. It is time to take the thirty-two steps home. But today it takes forty-seven because Able Bowers was washing his truck in the street and he tried to spray me, but even when I ran out of his reach I kept count. I try to be impeccably honest. I also try to avoid Able Bowers.

Dad is whistling 'Ain't We Got Fun' from the bathroom where he is washing his hands. When he hugs me I can smell the soap. The plate in the middle of the table is piled high with corn on the cob. It has a damp, sweet smell. I wish we could afford air conditioning. But when we take our seats and settle into the evening time, a coolness comes over us. Around our table we are safe. Dad is a rock. Mom is impenetrable. I hold hands with my little brothers, Jacob and Matt. They are so small and fair. I feel love for them pouring from my heart, all of a sudden, a reaction to the dark, fluffy tops of their heads bowed as Dad speaks. I am supposed to be praying.

Tonight I do not ask God for anything, I do not tell him what I hope is true. Tonight I say thanks. Here there simply is no war.